A version of this blog post can be found on the Tarides website: https://tarides.com/blog/2022-12-14-hillingar-mirageos-unikernels-on-nixos.

An arctic mirage[1]

The Domain Name System (DNS) is a critical component of the modern Internet, allowing domain names to be mapped to IP addresses, mailservers, and more2. This allows users to access services independent of their location in the Internet using human-readable names. We can host a DNS server ourselves to have authoritative control over our domain, protect the privacy of those using our server, increase reliability by not relying on a third party DNS provider, and allow greater customization of the records served (or the behaviour of the server itself). However, it can be quite challenging to deploy one's own server reliably and reproducibly, as I discovered during my master's thesis [2]. The Nix deployment system aims to address this. With a NixOS machine, deploying a DNS server is as simple as:

{

services.bind = {

enable = true;

zones."freumh.org" = {

master = true;

file = "freumh.org.zone";

};

};

}Which we can then query with

$ dig ryan.freumh.org @ns1.ryan.freumh.org +short

135.181.100.27To enable the user to query our domain

without specifying the nameserver, we have to create a glue record with

our registrar pointing ns1.freumh.org to the IP address of

our DNS-hosting machine.

You might notice this configuration is running the venerable bind3, which is written in C. As an alternative, using functional, high-level, type-safe programming languages to create network applications can greatly benefit safety and usability whilst maintaining performant execution [3]. One such language is OCaml.

MirageOS4 is a deployment method for these OCaml programs [4]. Instead of running them as a traditional Unix process, we instead create a specialised 'unikernel' operating system to run the application, which allows dead code elimination improving security with smaller attack surfaces and improved efficiency.

However, to deploy a Mirage unikernel with NixOS, one must use the imperative deployment methodologies native to the OCaml ecosystem, eliminating the benefit of reproducible systems that Nix offers. This blog post will explore how we enabled reproducible deployments of Mirage unikernels by building them with Nix.

At this point, the curious reader might be wondering, what is 'Nix'?

Nix is a deployment system that uses

cryptographic hashes to compute unique paths for components6 that are stored in a read-only

directory: the Nix store, at

/nix/store/<hash>-<name>. This provides several

benefits, including concurrent installation of multiple versions of a

package, atomic upgrades, and multiple user environments [5].

Nix uses a declarative domain-specific language (DSL), also called Nix, to build and configure software. The snippet used to deploy the DNS server is in fact a Nix expression. This example doesn't demonstrate it, but Nix is Turing complete. Nix does not, however, have a type system.

We use the DSL to write derivations for

software, which describe how to build said software with input

components and a build script. This Nix expression is then

'instantiated' to create 'store derivations' (.drv files),

which is the low-level representation of how to build a single

component. This store derivation is 'realised' into a built artefact,

hereafter referred to as 'building'.

Possibly the simplest Nix derivation uses

bash to create a single file containing

Hello, World!:

{ pkgs ? import <nixpkgs> { } }:

builtins.derivation {

name = "hello";

system = builtins.currentSystem;

builder = "${nixpkgs.bash}/bin/bash";

args = [ "-c" ''echo "Hello, World!" > $out'' ];

}Note that derivation is a function

that we're calling with one argument, which is a set of

attributes.

We can instantiate this Nix derivation to create a store derivation:

$ nix-instantiate default.nix

/nix/store/5d4il3h1q4cw08l6fnk4j04a19dsv71k-hello.drv

$ nix show-derivation /nix/store/5d4il3h1q4cw08l6fnk4j04a19dsv71k-hello.drv

{

"/nix/store/5d4il3h1q4cw08l6fnk4j04a19dsv71k-hello.drv": {

"outputs": {

"out": {

"path": "/nix/store/4v1dx6qaamakjy5jzii6lcmfiks57mhl-hello"

}

},

"inputSrcs": [],

"inputDrvs": {

"/nix/store/mnyhjzyk43raa3f44pn77aif738prd2m-bash-5.1-p16.drv": [

"out"

]

},

"system": "x86_64-linux",

"builder": "/nix/store/2r9n7fz1rxq088j6mi5s7izxdria6d5f-bash-5.1-p16/bin/bash",

"args": [ "-c", "echo \"Hello, World!\" > $out" ],

"env": {

"builder": "/nix/store/2r9n7fz1rxq088j6mi5s7izxdria6d5f-bash-5.1-p16/bin/bash",

"name": "hello",

"out": "/nix/store/4v1dx6qaamakjy5jzii6lcmfiks57mhl-hello",

"system": "x86_64-linux"

}

}

}And build the store derivation:

$ nix-store --realise /nix/store/5d4il3h1q4cw08l6fnk4j04a19dsv71k-hello.drv

/nix/store/4v1dx6qaamakjy5jzii6lcmfiks57mhl-hello

$ cat /nix/store/4v1dx6qaamakjy5jzii6lcmfiks57mhl-hello

Hello, World!Most Nix tooling does these two steps together:

nix-build default.nix

this derivation will be built:

/nix/store/q5hg3vqby8a9c8pchhjal3la9n7g1m0z-hello.drv

building '/nix/store/q5hg3vqby8a9c8pchhjal3la9n7g1m0z-hello.drv'...

/nix/store/zyrki2hd49am36jwcyjh3xvxvn5j5wml-helloNix realisations (hereafter referred to as 'builds') are done in isolation to ensure reproducibility. Projects often rely on interacting with package managers to make sure all dependencies are available and may implicitly rely on system configuration at build time. To prevent this, every Nix derivation is built in isolation (without network access or access to the global file system) with only other Nix derivations as inputs.

The name Nix is derived from the Dutch word niks, meaning nothing; build actions do not see anything that has not been explicitly declared as an input [5].

You may have noticed a reference to

nixpkgs in the above derivation. As every input to a Nix

derivation also has to be a Nix derivation, one can imagine the tedium

involved in creating a Nix derivation for every dependency of your

project. However, Nixpkgs7 is a large repository of software

packaged in Nix, where a package is a Nix derivation. We can use

packages from Nixpkgs as inputs to a Nix derivation, as we've done with

bash.

There is also a command line package manager installing packages from Nixpkgs, which is why people often refer to Nix as a package manager. While Nix, and therefore Nix package management, is primarily source-based (since derivations describe how to build software from source), binary deployment is an optimisation of this. Since packages are built in isolation and entirely determined by their inputs, binaries can be transparently deployed by downloading them from a remote server instead of building the derivation locally.

NixOS, 9 is a Linux distribution built

with Nix from a modular, purely functional specification [6]. It has no traditional filesystem

hierarchy (FSH), like /bin, /lib,

/usr, but instead stores all components in

/nix/store. The system configuration is managed by Nix and

configured with Nix expressions. NixOS modules are Nix files containing

chunks of system configuration that can be composed to build a full

NixOS system10. While many NixOS modules are

provided in the Nixpkgs repository, they can also be written by an

individual user. For example, the expression used to deploy a DNS server

is a NixOS module. Together these modules form the configuration which

builds the Linux system as a Nix derivation.

NixOS minimises global mutable state that -- without knowing it -- you might rely on being set up in a certain way. For example, you might follow instructions to run a series of shell commands and edit some files to get a piece of software working. You may subsequently be unable to reproduce the result because you've forgotten some intricacy or are now using a different version of the software. Nix forces you to encode this in a reproducible way, which is extremely useful for replicating software configurations and deployments, aiming to solve the 'It works on my machine' problem. Docker is often used to fix this configuration problem, but Nix aims to be more reproducible. This can be frustrating at times because it can make it harder to get a project off the ground, but I've found the benefits outweigh the downsides, personally.

My own NixOS configuration is publicly

available11. This makes it simple to reproduce

my system (a collection of various hacks, scripts, and workarounds) on

another machine. I use it to manage servers, workstations, and more.

Compared to my previous approach of maintaining a Git repository of

dotfiles, this is much more modular, reproducible, and

flexible. And if you want to deploy some new piece of software or

service, it can be as easy as changing a single line in your system

configuration.

Despite these advantages, the reason I

switched to NixOS from Arch Linux was simpler: NixOS allows rollbacks

and atomic upgrades. As Arch packages bleeding-edge software with

rolling updates, it would frequently happen that some new version of

something I was using would break. Arch has one global coherent package

set, so to avoid complications with solving dependency versions Arch

doesn't support partial upgrades. Given this, the options were to wait

for the bug to be fixed or manually rollback all the updated packages by

inspecting the pacman log (the Arch package manager) and

reinstalling the old versions from the local cache. While there may be

tools on top of pacman to improve this, the straw that

broke the camel's back was when my machine crashed while updating the

Linux kernel, and I had to reinstall it from a live USB.

While Nixpkgs also has one global coherent package set, one can use multiple instances of Nixpkgs (i.e., channels) at once to support partial upgrades, as the Nix store allows multiple versions of a dependency to be stored. This also supports atomic upgrades, as all the software's old versions can be kept until garbage collection. The pointers to the new packages are only updated when the installation succeeds, so the crash during the Linux kernel upgrade would not have broken my OS install on NixOS. And every new system configuration creates a GRUB entry, so you can boot previous systems even from your UEFI/BIOS.

To summarise the parts of the Nix ecosystem that we've discussed:

We also use Nix flakes for this project.

Without going into too much depth, they enable hermetic evaluation of

Nix expressions and provide a standard way to compose Nix projects. With

flakes, instead of using a Nixpkgs repository version from a 'channel'12, we pin Nixpkgs as an input to

every Nix flake, be it a project build with Nix or a NixOS system.

Integrated with flakes, there is also a new nix command

aimed at improving the UI of Nix. You can read more detail about flakes

in a series of blog posts by Eelco on the topic13.

MirageOS is a library operating system that allows users to create unikernels, which are specialized operating systems that include both low-level operating system code and high-level application code in a single kernel and a single address space.[4].

It was the first such 'unikernel creation framework', but comes from a long lineage of OS research, such as the exokernel library OS architecture [7]. Embedding application code in the kernel allows for dead-code elimination, removing OS interfaces that are unused, which reduces the unikernel's attack surface and offers improved efficiency.

Mirage unikernels are written OCaml15. OCaml is more practical for systems programming than other functional programming languages, such as Haskell. It supports falling back on impure imperative code or mutable variables when warranted.

Now that we understand what Nix and Mirage are, and we've motivated the desire to deploy Mirage unikernels on a NixOS machine, what's stopping us from doing just that? Well, to support deploying a Mirage unikernel, like for a DNS server, we would need to write a NixOS module for it.

A paired-down16 version of the bind NixOS module, the module used in our Nix expression for deploying a DNS server on NixOS (§), is:

{ config, lib, pkgs, ... }:

with lib;

{

options = {

services.bind = {

enable = mkEnableOption "BIND domain name server";

zones = mkOption {

...

};

};

};

config = mkIf cfg.enable {

systemd.services.bind = {

description = "BIND Domain Name Server";

after = [ "network.target" ];

wantedBy = [ "multi-user.target" ];

serviceConfig = {

ExecStart = "${pkgs.bind.out}/sbin/named";

};

};

};

}Notice the reference to

pkgs.bind. This is the Nixpkgs repository Nix derivation

for the bind package. Recall that every input to a Nix

derivation is itself a Nix derivation (§); in

order to use a package in a Nix expression -- i.e., a NixOS module -- we

need to build said package with Nix. Once we build a Mirage unikernel

with Nix, we can write a NixOS module to deploy it.

Mirage uses the package manager for OCaml called opam17. Dependencies in opam, as is common in programming language package managers, have a file which -- among other metadata, build/install scripts -- specifies dependencies and their version constraints. For example18

...

depends: [

"arp" { ?monorepo & >= "3.0.0" & < "4.0.0" }

"ethernet" { ?monorepo & >= "3.0.0" & < "4.0.0" }

"lwt" { ?monorepo }

"mirage" { build & >= "4.2.0" & < "4.3.0" }

"mirage-bootvar-solo5" { ?monorepo & >= "0.6.0" & < "0.7.0" }

"mirage-clock-solo5" { ?monorepo & >= "4.2.0" & < "5.0.0" }

"mirage-crypto-rng-mirage" { ?monorepo & >= "0.8.0" & < "0.11.0" }

"mirage-logs" { ?monorepo & >= "1.2.0" & < "2.0.0" }

"mirage-net-solo5" { ?monorepo & >= "0.8.0" & < "0.9.0" }

"mirage-random" { ?monorepo & >= "3.0.0" & < "4.0.0" }

"mirage-runtime" { ?monorepo & >= "4.2.0" & < "4.3.0" }

"mirage-solo5" { ?monorepo & >= "0.9.0" & < "0.10.0" }

"mirage-time" { ?monorepo }

"mirageio" { ?monorepo }

"ocaml" { build & >= "4.08.0" }

"ocaml-solo5" { build & >= "0.8.1" & < "0.9.0" }

"opam-monorepo" { build & >= "0.3.2" }

"tcpip" { ?monorepo & >= "7.0.0" & < "8.0.0" }

"yaml" { ?monorepo & build }

]

...Each of these dependencies will have its own dependencies with their own version constraints. As we can only link one dependency into the resulting program, we need to solve a set of dependency versions that satisfies these constraints. This is not an easy problem. In fact, it's NP-complete [8]. Opam uses the Zero Install19 SAT solver for dependency resolution.

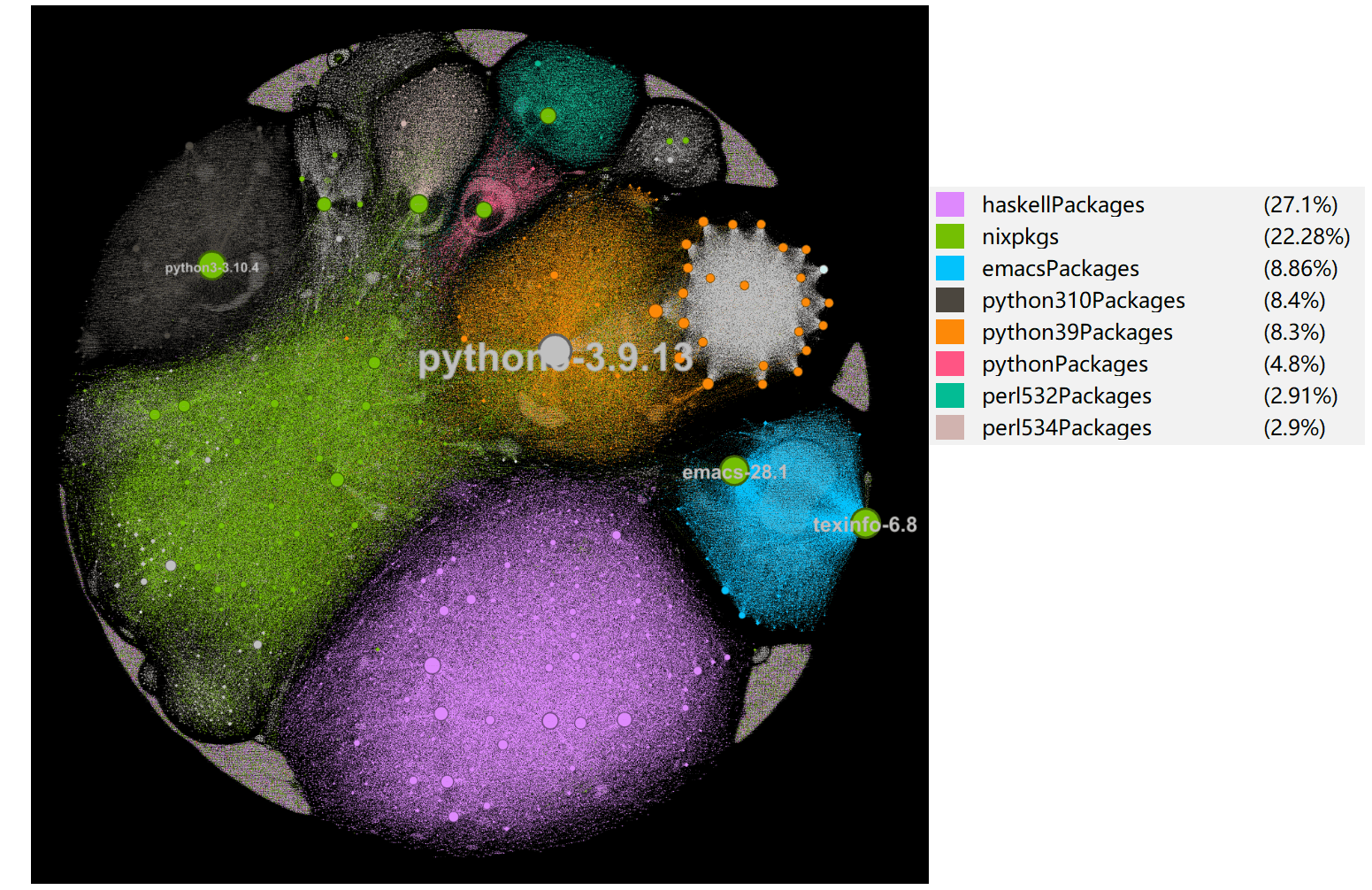

Nixpkgs has many OCaml packages20 which we could provide as build inputs to a Nix derivation21. However, Nixpkgs has one global coherent set of package versions22, 23. The support for installing multiple versions of a package concurrently comes from the fact that they are stored at a unique path and can be referenced separately, or symlinked, where required. So different projects or users that use a different version of Nixpkgs won't conflict, but Nix does not do any dependency version resolution -- everything is pinned24. This is a problem for opam projects with version constraints that can't be satisfied with a static instance of Nixpkgs.

Luckily, a project from Tweag

already exists (opam-nix) to deal with this25, 26. This project uses the opam

dependency versions solver inside a Nix derivation, and then creates

derivations from the resulting dependency versions27.

This still doesn't support

building our Mirage unikernels, though. Unikernels quite often need to

be cross-compiled: compiled to run on a platform other than the one

they're being built on. A common target, Solo528,

is a sandboxed execution environment for unikernels. It acts as a

minimal shim layer to interface between unikernels and different

hypervisor backends. Solo5 uses a different glibc which

requires cross-compilation. Mirage 429 supports cross

compilation with toolchains in the Dune build system30.

This uses a host compiler installed in an opam switch (a virtual

environment) as normal, as well as a target compiler31.

But the cross-compilation context of packages is only known at build

time, as some metaprogramming modules may require preprocessing with the

host compiler. To ensure that the right compilation context is used, we

have to provide Dune with all our sources' dependencies. A tool called

opam-monorepo was created to do just that32.

We extended the

opam-nix project to support the opam-monorepo

workflow with this pull request: github.com/tweag/opam-nix/pull/18.

This is very low-level support

for building Mirage unikernels with Nix, however. In order to provide a

better user experience, we also created the Hillinar Nix flake: github.com/RyanGibb/hillingar.

This wraps the Mirage tooling and opam-nix function calls

so that a simple high-level flake can be dropped into a Mirage project

to support building it with Nix. To add Nix build support to a

unikernel, simply:

# create a flake from hillingar's default template

$ nix flake new . -t github:/RyanGibb/hillingar

# substitute the name of the unikernel you're building

$ sed -i 's/throw "Put the unikernel name here"/"<unikernel-name>"/g' flake.nix

# build the unikernel with Nix for a particular target

$ nix build .#<target>For example, see the flake for building the Mirage website as a unikernel with Nix: github.com/RyanGibb/mirage-www/blob/master/flake.nix.

To step back for a moment and look at the big picture, we can consider a number of different types of dependencies at play here:

depexts in opam parlance. This is

Nix for Hillinar, but another platform's package managers include

apt, pacman, and brew. For

unikernels, these are often C libraries like gmp.opam,

pip, and npm. These are the dependencies that

often have version constraints and require resolution possibly using a

SAT solver.a calls function b, then a

'depends' on b. This is the level of granularity that

compilers and interpreters are normally concerned with. In the realms of

higher-order functions this dependance may not be known in advance, but

this is essentially the same problem that build systems face with

dynamic dependencies [9].Nix deals well with system dependencies, but it doesn't have a native way of resolving library dependency versions. Opam deals well with library dependencies, but it doesn't have a consistent way of installing system packages in a reproducible way. And Dune deals with file dependencies, but not the others. The OCaml compiler keeps track of function dependencies when compiling and linking a program.

Dune is used to support

cross-compilation for Mirage unikernels (§). We encode the cross-compilation

context in Dune using the preprocess stanza from Dune's

DSL, for example from mirage-tcpip:

(library

(name tcp)

(public_name tcpip.tcp)

(instrumentation

(backend bisect_ppx))

(libraries logs ipaddr cstruct lwt-dllist mirage-profile tcpip.checksum

tcpip duration randomconv fmt mirage-time mirage-clock mirage-random

mirage-flow metrics)

(preprocess

(pps ppx_cstruct)))Which tells Dune to preprocess

the opam package ppx_cstruct with the host compiler. As

this information is only available from the build manager, this requires

fetching all dependency sources to support cross-compilation with the

opam-monorepo tool:

Cross-compilation - the details of how to build some native code can come late in the pipeline, which isn't a problem if the sources are available33.

This means we're essentially

encoding the compilation context in the build system rules. To remove

the requirement to clone dependency sources locally with

opam-monorepo we could try and encode the compilation

context in the package manager. However, preprocessing can be at the

OCaml module level of granularity. Dune deals with this level of

granularity with file dependencies, but opam doesn't. Tighter

integration between the build and package manager could improve this

situation, like Rust's Cargo. There are some plans towards modularising

opam and creating tighter integration with Dune.

There is also the possibility of using Nix to avoid cross-compilation. Nixpkg's cross compilation34 will not innately help us here, as it simply specifies how to package software in a cross-compilation friendly way. However, Nix remote builders would enable reproducible builds on a remote machine35 with Nix installed that may sidestep the need for cross-compilation in certain contexts.

Hillingar uses the Zero Install

SAT solver for version resolution through opam. While this works, it

isn't the most principled approach for getting Nix to work with library

dependencies. Some package managers are just using Nix for system

dependencies and using the existing tooling as normal for library

dependencies36. But generally, X2nix

projects are numerous and created in an ad hoc way. Part of

this is dealing with every language's ecosystems package repository

system, and there are existing approaches37, 38 aimed at reducing code

duplication, but there is still the fundamental problem of version

resolution. Nix uses pointers (paths) to refer to different versions of

a dependency, which works well when solving the diamond dependency

problem for system dependencies, but we don't have this luxury when

linking a binary with library dependencies.

This is exactly why opam uses a

constraint solver to find a coherent package set. But what if we could

split version-solving functionality into something that can tie into any

language ecosystem? This could be a more principled, elegant, approach

to the current fragmented state of library dependencies (program

language package managers). This would require some ecosystem-specific

logic to obtain, for example, the version constraints and to create

derivations for the resulting sources, but the core functionality could

be ecosystem agnostic. As with opam-nix, materialization39 could be used to commit a lock file

and avoid IFD. Although perhaps this is too lofty a goal to be

practical, and perhaps the real issues are organisational rather than

technical.

Nix allows multiple versions of

a package to be installed simultaneously by having different derivations

refer to different paths in the Nix store concurrently. What if we could

use a similar approach for linking binaries to sidestep the version

constraint solving altogether at the cost of larger binaries? Nix makes

a similar tradeoff makes with disk space. A very simple approach might

be to programmatically prepend/append functions in D with

the dependency version name vers1 and vers2

for calls in the packages B and C respectively

in the diagram above.

Another way to avoid NP-completeness is to attack assumption 4: what if two different versions of a package could be installed simultaneously? Then almost any search algorithm will find a combination of packages to build the program; it just might not be the smallest possible combination (that's still NP-complete). If

BneedsD1.5 andCneeds D 2.2, the build can include both packages in the final binary, treating them as distinct packages. I mentioned above that there can't be two definitions ofprintfbuilt into a C program, but languages with explicit module systems should have no problem including separate copies ofD(under different fully-qualified names) into a program. [8]

Another wackier idea is, instead of having programmers manually specific constraints with version numbers, to resolve dependencies purely based on typing40. The issue here is that solving dependencies would now involve type checking, which could prove computationally expensive.

The build script in a Nix derivation (if it doesn't invoke a compiler directly) often invokes a build system like Make, or in this case Dune. But Nix can also be considered a build system with a suspending scheduler and deep constructive trace rebuilding [9]. But Nix is at a coarse-grained package level, invoking these finer-grained build systems to deal with file dependencies.

In Chapter 10 of the original Nix thesis [10], low-level build management using Nix is discussed, proposing extending Nix to support file dependencies. For example, to build the ATerm library:

{sharedLib ? true}:

with (import ../../../lib);

rec {

sources = [

./afun.c ./aterm.c ./bafio.c ./byteio.c ./gc.c ./hash.c

./list.c ./make.c ./md5c.c ./memory.c ./tafio.c ./version.c

];

compile = main: compileC {inherit main sharedLib;};

libATerm = makeLibrary {

libraryName = "ATerm";

objects = map compile sources;

inherit sharedLib;

};

}This has the advantage over traditional build systems like Make that if a dependency isn't specified, the build will fail. And if the build succeeds, the build will succeed. So it's not possible to make incomplete dependency specifications, which could lead to inconsistent builds.

A downside, however, is that Nix doesn't support dynamic dependencies. We need to know the derivation inputs in advance of invoking the build script. This is why in Hillingar we need to use IFD to import from a derivation invoking opam to solve dependency versions.

There is prior art that aims to support building Dune projects with Nix in the low-level manner described called tumbleweed. While this project is now abandoned, it shows the difficulties of trying to work with existing ecosystems. The Dune build system files need to be parsed and interpreted in Nix, which either requires convoluted and error-prone Nix code or painfully slow IFD. The former approach is taken with tumbleweed which means it could potentially benefit from improving the Nix language. But fundamentally this still requires the complex task of reimplementing part of Dune in another language.

I would be very interested if anyone reading this knows if this idea went anywhere! A potential issue I see with this is the computational and storage overhead associated with storing derivations in the Nix store that are manageable for coarse-grained dependencies might prove too costly for fine-grained file dependencies.

While on the topic of build systems, to enable more minimal builds tighter integration with the compiler would enable analysing function dependencies41. For example, Dune could recompile only certain functions that have changed since the last invocation. Taking granularity to such a fine degree will cause a great increase in the size of the build graph, however. Recomputing this graph for every invocation may prove more costly than doing the actual rebuilding after a certain point. Perhaps persisting the build graph and calculating differentials of it could mitigate this. A meta-build-graph, if you will.

Hillingar's primary limitations are (1)

complex integration is required with the OCaml ecosystem to solve

dependency version constraints using opam-nix, and (2) that

cross-compilation requires cloning all sources locally with

opam-monorepo (§).

Another issue that proved an annoyance during this project is the Nix

DSL's dynamic typing. When writing simple derivations this often isn't a

problem, but when writing complicated logic, it quickly gets in the way

of productivity. The runtime errors produced can be very hard to parse.

Thankfully there is work towards creating a typed language for the Nix

deployment system, such as Nickel42. However, gradual

typing is hard, and Nickel still isn't ready for real-world use despite

being open-sourced (in a week as of writing this) for two

years.

A glaring omission is that despite it being the primary motivation, we haven't actually written a NixOS module for deploying a DNS server as a unikernel. There are still questions about how to provide zonefile data declaratively to the unikernel, and manage the runtime of deployed unikernels. One option to do the latter is Albatross43, which has recently had support for building with nix added44. Albatross aims to provision resources for unikernels such as network access, share resources for unikernels between users, and monitor unikernels with a Unix daemon. Using Albatross to manage some of the inherent imperative processes behind unikernels, as well as share access to resources for unikernels for other users on a NixOS system, could simplify the creation and improve the functionality of a NixOS module for a unikernel.

There also exists related work in the reproducible building of Mirage unikernels. Specifically, improving the reproducibility of opam packages (as Mirage unikernels are opam packages themselves)45. Hillingar differs in that it only uses opam for version resolution, instead using Nix to provide dependencies, which provides reproducibility with pinned Nix derivation inputs and builds in isolation by default.

To summarise, this project was motivated

(§) by deploying unikernels on NixOS (§). Towards this end, we added support

for building MirageOS unikernels with Nix; we extended

opam-nix to support the opam-monorepo workflow

and created the Hillingar project to provide a usable Nix interface (§). This required scrutinising the OCaml

and Nix ecosystems along the way in order to marry them; some thoughts

on dependency management were developed in this context (§). Many strange issues and edge cases

were uncovered during this project but now that we've encoded them in

Nix, hopefully, others won't have to repeat the experience!

While only the first was the primary motivation, the benefits of building unikernels with Nix are:

conf-gmp is a 'virtual package' that relies on a system

installation of the C/Assembly library gmp (The GNU

Multiple Precision Arithmetic Library). Nix easily allows us to depend

on this package in a reproducible way.While NixOS and MirageOS take fundamentally very different approaches, they're both trying to bring some kind of functional programming paradigm to operating systems. NixOS does this in a top-down manner, trying to tame Unix with functional principles like laziness and immutability46; whereas, MirageOS does this by throwing Unix out the window and rebuilding the world from scratch in a very much bottom-up approach. Despite these two projects having different motivations and goals, Hillingar aims to get the best from both worlds by marrying the two.

I want to thank some people for their help with this project:

opam-nix project and working with me on the

opam-monorepo workflow integration.This work was completed with the support of Tarides.

If you spot any errors, have any questions, notice something I've mentioned that someone has already thought of, or notice any incorrect assumptions or assertions made, please get in touch at ryan@freumh.org.

If you have a unikernel, consider trying to build it with Hillingar, and please report any problems at github.com/RyanGibb/hillingar/issues!

Generated with Stable Diffusion and GIMP↩︎

As 'nix' means snow in Latin. Credits to Tim Cuthbertson.↩︎

NB: we will use component, dependency, and package somewhat interchangeably in this blog post, as they all fundamentally mean the same thing -- a piece of software.↩︎

nixos.org/manual/nix/stable/package-management/channels.html↩︎

Credits to Takayuki Imada↩︎

Barring the use of foreign function interfaces (FFIs).↩︎

For mirage-www targetting

hvt.↩︎

NB they are not

as complete nor up-to-date as those in opam-repository github.com/ocaml/opam-repository.↩︎

Bar some exceptional packages that have multiple major versions packaged, like Postgres.↩︎

In fact Arch has the same approach, which is why it doesn't support partial upgrades (§).↩︎

This has led to much confusion with how to install a specific version of a package github.com/NixOS/nixpkgs/issues/9682.↩︎

Another project, timbertson/opam2nix, also exists but depends on a binary of itself at build time as it's written in OCaml as opposed to Nix, is not as minimal (higher LOC count), and it isn't under active development (with development focused on github.com/timbertson/fetlock)↩︎

Using something called Import From Derivation (IFD) nixos.wiki/wiki/Import_From_Derivation. Materialisation can be used to create a kind of lock file for this resolution, which can be committed to the project to avoid having to do IFD on every new build. An alternative may be to use opam's built-in version pinning27.↩︎

nixos.org/manual/nix/stable/advanced-topics/distributed-builds.html↩︎